Kiki Smith: Flight Mound

At the Mattress Factory

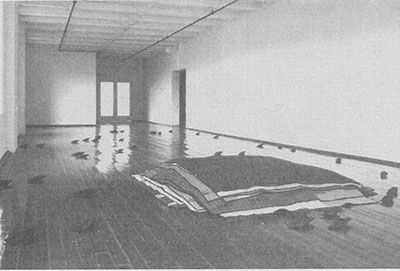

Flight Mound 1998. Installation of silkscreened packing quilts and bronze birds at the Mattress Factory in Pittsburgh, PA.

Body of Work

By Karen Tom. Photos: Robert Baldridge in COVER Magazine, 1998 issue.

The mission began on February 4, 1998, 12:32 a.m., New York City. There were flash-flood warnings for the entire East Coast. Noreaster was in full force, but despite the obstacles, my partner-in-crime, photographer Robert Baldridge and I packed up our gear and resolutely headed on the icy highways and byways, pilgrimaging to Pittsburgh.

Between driving shifts and insomnia, I zoned into the world of Kiki Smith. Under the guidance of a flashlight, I read through the one-inch pile of articles about Kiki's life and career. The information mostly covered her multi medium sculptures exploring the human anatomy and its functions, via excretions and exposed organs. A study she spent over a decade dissecting.

It catapulted her into the art world spotlight — a prestige that includes representation by the one of the world's most prestigious galleries, the Pace Wildenstein Gallery; solo exhibitions at the MoMA, Dallas Museum of Art, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles; group showings at The Whitney Biennial, New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York, Guggenheim Museum SoHo, and her bronze version of Lilith permanently displayed at the MET.

Also, I learned the details of her personal history: the life of being the daughter of artist Tony Smith, an environment with Jackson Pollack and Lee Krasner as casual guests at the dinner table.

In things like art you don't have to have any direction where you are trying to go, so you just go to towards what attracts you or compels you to move.

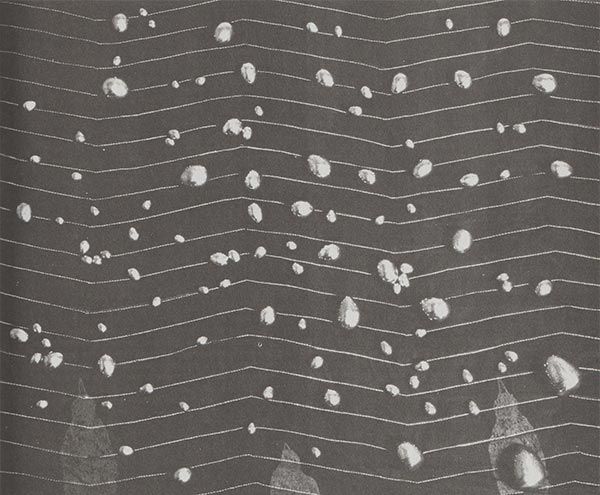

The only information missing was background on her fairly recent transition to the avian subject matter; in which her Mattress Factory installation focused on mainly silk-screened birds on quilts. Other elements included cast iron birds and eggs, and a film re-animation of Eadweard Muybridge's 1885 photographic sequence of birds in flight. All I knew was that she liked birds, and was exploring them through various mediums

Dickens thought the steel-mill city of Pittsburgh resembled Hell with its lid off. The drama in the landscape emitted a mysterious Masonic ambiance, with a feel of decaying potential. It offered the appropriate random backdrop to the attic-esque feeling of the space in which Kiki spread out her 68 silkscreened quilts and flock of birds.

Sinisterly solemn, the black cast iron birds lay spread out, facing one direction, surrounding a multi-colored mound of quilts with silk-screened birds. In the adjoining space, was a projected black and white image on approximately 9'x 12' screen of a bird in frontal torso view, wings spread and in flight. The bird's size magnified, filling the screen. The image left a subtle glow to the room, and a semblance of peace. At the other end, located in the center of the cemented walls, under a dim bulb that hangs a foot from the floor, laid a collection of shiny bronzed eggs, like an archaeological secret uncovered.

Flight Mound detail

TOM: The Mattress Factory is a site-specific installation space. What led you to bring your quilts here?

SMITH: They asked me if I wanted to have the opportunity to make something for this floor, and this is just what I wanted to make. I wanted to make packing blankets, and this seemed like the opportunity to do it because they could organize the labor of it. It's a lot of work and I couldn't do it on my own.

TOM: What started you on quilt making?

SMITH: I made quilts since I was a teenager, making them for my private use. I liked the packing blankets because they were a random way that color and patterns are put together. I thought it was nice to look at, and a way to think about how to organize color.

TOM: What would you say separates art and craft?

SMITH: I would imagine intentional separation.

TOM: What spurred the transition to use birds as your representation of nature?

SMITH: I always have kept birds and as I a child I kept birds. I like thinking about them. I like them, and it just started happening. In things like art you don't have to have any direction where you are trying to go, so you just go to towards what attracts you or compels you to move. I just needed more space than just the body to work in. Also, I was interested in cosmology stories involving humans and animals, and from there I went into making animals.

TOM: Birds are very spiritually symbolic; do you feel that emotion in your life as well as art?

SMITH: Birds traditionally do have a spiritual symbolism in relationship to death; this is literally a death of birds, death of natural habitat more than I mean it as metaphorical death of humans. In this time of displacement of many species and living things losing habitat, and the loss of other life forms, I don't mean it in relationship to humans; I just mean it in relationship to birds.

TOM: What other mediums do you look forward to exploring?

SMITH: I would like to make things out of plastic I don't have any super ideas of what to do with plastic, resin and things like that. I don't like working personally with toxic materials, nor do I want to espouse the use of toxic materials for other people. I would also like to do some work in clay; do ceramics work more.

TOM: Is this your first video piece?

SMITH: I use to make films when I was younger. I studied film in school and made some in the late 70s and early 80s. I did films on nature phenomenon. I made a film with Carol Perlman and Ellen Cooper called Tu/aux, which was a spoof detective story. I made another film with Ellen Cooper called Cavegirl. It was a science-fiction story. I made a film about making butter.

TOM: You work so much with you hands, how do you feel about the new art techniques and computer generated images?

SMITH: I think it's great. It's just another medium. It's like a new space people can experiment in it, see what the limits of it are and then it becomes a known space like oil paint or something like that. It's just another exploration, another possibility. It's all technology. People used their hands to make hand-made things because that was the contemporary technology and then people make new technologies. I like old technologies because I have a sense of it like it's a vacant space. It has no power in it in a certain way because it is unnecessary in most aspects of life, like ceramics jars when you could make plastic jars. In a way it has a kind of freedom in it because nobody needs it anymore. It's all just tools.

TOM: If you could live in any time period, which would you choose and as what?

SMITH: I would probably like to be a jeweler, or a cook, maybe a ceramist in some period, like the Chang Dynasty, or the arts and craft movement in England. There are so many choices in the whole history of the world. There are so many interesting aspects. Some are more counteractive and some are more expansive than others. There are certainly times of terror where one, if given the choice to choose, would avoid. There is a lot to learn. That's why I go to museums and see all the information that people already know about how to make a physical expression.

TOM: What would you like to come into your next life as?

SMITH: All I could hope is I'll learn what I'm to learn properly in this lifetime, and that I don't come back lower than this, and that I will, at least, keep progressing spiritually. I leave it up to whatever I have invested in this lifetime.