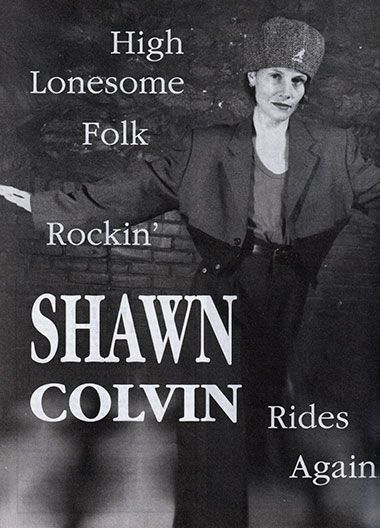

A Conversation with Singer Songwriter Shawn Colvin

Colvin in Comme des Garcons, 1995

Steady On

By Jeffrey Cyphers Wright. Photography: Bob Berg

Location: Toad Hall, New Haven, CT

In COVER Holiday issue 1996

Grammy winner Shawn Colvin has developed a huge fan base over the last decade with her soulful songwriting and high lonesome rock voice. She's currently on a nationwide tour supporting a solo album of her greatest hits. Few singers posses the ability to mesmerize audiences and create a special one-on-one feeling. Shawn's voice, wounded, angelic, glides and hangs onto the guitar notes keeping you right there with its narcotic, uplifting punch.

JCW: I didn't realize you lived in South Dakota...

SC: 'Til I was 11. We moved to London, Ontario for two years, then Carbondale, Illinois and I went to high school there. Spent another ten years there.

JCW: The term heartland applies to you.

SC: Yeah. it's true.

JCW: Another person I think of as the heartland sound is John Mellencamp.

SC: I liked his record called The Lonesome Jubilee. That's the record I got into him on. He used the instrumentation and this band in a rootsy way that sounded different than the way anyone used it before, he synthesized things, and gave everybody specific parts and it was just beautiful.

JCW: You’re more stripped down in a way.

SC: I just kind of take it song by song. I can see in that record he went for an overall approach. In the past I've had musicians come in for different songs, but on this one I'm going to have a band.

JCW: Your last album was a daring release of cover songs. Are all the songs going to be yours this time?

SC: I might do one or two covers, but the one I can tell you might be a James Tippery song.

JCW: I didn't realize you had won your Grammy in the folk category. I never thought of you as folk.

SC: Good. It's called contemporary folk. It's kind of lucky that there's a category like that. It provides a place for me to get some attention in a scene where I kind of fall through the cracks, in terms of radio. I'm not alternative, pop, hard rock, I'm not the lite rock thing. In the past few years there's been a radio format called triple adult album alternative thing. That's been good for me.

JCW: Have you been on VHl?

SC: I’ve been on VHl when my first record came out. They were experimenting with their format. They played a lot of wild stuff, Subdudes, Bela Flek, but by the time my record came out it was oldies/top 40. Now they've widened up a little more but MTV's never played me, I'm too old. I fall between the cracks in many ways. It's not that I don't think there's a solution to this.

...as an artist you have to, as idealistic as it may seem, you have to feel like you are the next big thing.

JCW: Did you have a radio hit?

SC: No. I've toured relentlessly and I've built a following based on the fact that I play a lot and I like to believe I put on a good show and that's helped me tremendously.

JCW: And you enjoy it?

SC: I enjoy it but it's getting a little old, like 250 days a year.

JCW: Talking about this folk stuff I keep flashing on that song Dylan did at the Newport Festival. "I Ain't Gonna Work on Maggie's Farm No More." Did that have any resonance For you?

SC: It was before I was really into it. I didn't really closely follow Dylan until Blood on the Tracks came out. So I only know about that incident in hindsight but it's a great incident to know about. They booed Dylan for Highway 61.

JCW: But that's kind of a fight we're still having to fight

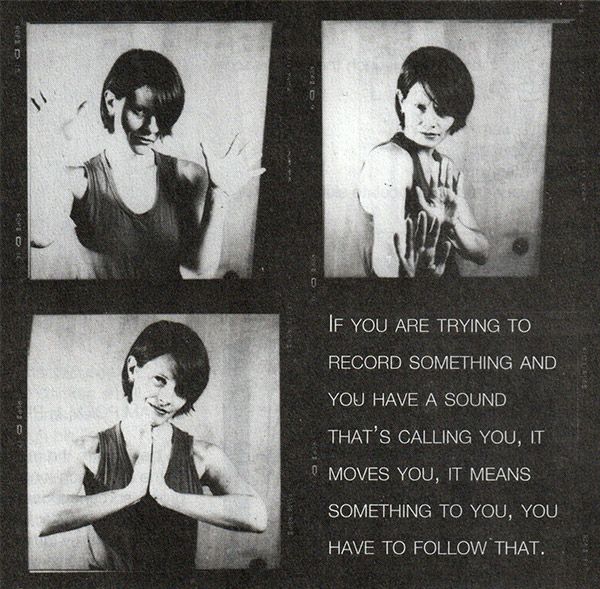

SC: The fight is to keep doing the music you want to do and not second guess yourself by whatever's going on on the radio. The mentality seems to be that the record company for the most part is going to play it safe and think about where to market you in terms of whoever is very marketable at the moment. But as an artist you have to, as idealistic as it may seem, you have to feel like you are the next big thing. If you are trying to record something and you have a sound that's calling you, it moves you, it means something to you, you have to follow that. I haven't always done that, I have compromised in favor of the record company, I've tried to play my cards appropriately and keep people happy, and it's been a valuable lesson, but I'm done with that.

JCW: Tell me about your favorite guitars.

SC: I'm not a guitar nut like most of the guys I've worked with. I like my Martin guitar. I like ouden guitars. In electric, Fenders seem easy to play and they have a good sound. I like the sound of a dobro played like a guitar.

The lyric is the focus, or the feeling behind the lyric.

JCW: "Crossover" is another term like heartland that's been applied to you. How do you feel about the term?

SC: My understanding of that term has to do with being a hit in one genre and crossing over to another so it wouldn't really apply to me. I don't know what the term is when someone is a little bit this, a little bit that. Labels are important to the business and I don't have any illusions about that. The singer/songwriter monniker was what I grew up with. It was people like Joni Mitchell, James Taylor, Van Morrison, Laura Nyro, and that’s what I alway felt was the most appropriate. It gives the idea that you write your own songs. You probably play guitar, it might sound a little rock and roll, blues, country. The lyric is the focus, or the feeling behind the lyric. The artists that interest me most are in that no man's land.

JCW: Do you like to party?

SC: No. I'm old. I'm 39. I lived on the east-side. I partied my share, believe me. I came to New York December, 1980. The week before John Lennon got killed.

Colvin shoot, 1996

JCW: You were playing hard rock?

SC: It's kind of haunted me. I had a rock band in college. We just played bars and I was drinking and smoking and playing five hours a night and I blew my voice out. It was a cover band, a bar band, no big deal. I played bluegrass band & country swing bands and then l played by myself a bunch when I came to New York. l actually joined a kind of country rock band, it was real popular at the time and it was a job. That's how I got here, in the Buddy Miller band, Buddy Miller left and I took over.

JCW: There was a city folk resurgence.

SC: There was a club on 7th Avenue called City Limits.

JCW: Suzane Vega played there.

SC: I was actually not in on that primarily because I didn't consider myself folk. I met John Leventhal and it proved to be a really important relalationship. We were romantically involved. and he was in this cool band but they didn't know where they were going. He would give me pieces of music to work on. I had already written a couple of folky type songs over the years. We wrote some kind of sub par pop tunes and then I wrote "Diamond in the Rough" to one of the pieces of music he'd given me. That was the one where I took his demo and transferred it to the guitar and tried to put my folk/newly acquired Richard Thompson influence on what he'd given me, and for the first time in the four years we'd been trying to write tunes, l wrote something personal which I hadn't done. I had been trying to write clever Elvis Costello meets Steely Dan type of shit and we both realized that this was the thing. lt was another year or two but pretty soon after came “Cry Like An Angel.” We knew we were stockpiling this good Stuff. I got a deal.

JCW: How did that magic moment happen, A&R in the crowds?

SC: No, no, no. There was a little bit of a buzz going on. Boston college radio was really good to me. It's got a folk/song writer tradition. So I had a good following in Boston with no records, no deals. I signed on with my manager Ron Fierstein. His partner went out to shop a tape for another artist, but the record label (Columbia) asked if they had anything else. So that was 1988.

JCW: So you were here for eight years before you made it. Were there dark moments?

SC: I never thought I'd make it. Maybe one of the good things that happened to me was that I wasn't so bound and determined to make it that I... There were opportunities where I could have made some dodgy deals being someone's idea of a new chick singer. There were opportunities but they didn't seem right to me. I knew I was either going to rise to the occasion and try to be an artist and do the work, do the writing, and dig into my soul. It was either going to happen or it wasn’t. As much as I'd been working, doing live performance, I wasn't really a professional in that I had no goal in terms of recording.

There were opportunities where I could have made some dodgy deals being someone's idea of a new chick singer.

The focus just wasn’t coming. I was ten years into it and it just wasn't coming. I quit for a year and during that year I was fully prepared to hang the whole thing up forever. I thought, "What have you always done best? And l said to myself, “You’ve always done best when you’ve played by yourself.” I’ve always felt this certain power when I would just get up and play by myself. That’s how I ended up writing "Diamond in the Rough.” I figured to play on my own. That’s the litmus test ever since. It yields what's true to me. I don't get sick of it, I don't doubt myself. I don't think about what do other people want or particularly care about being criticized, but I found my voice.

JCW: The songs are so beautiful, not just sad but upbeat and uplifting ... not downers.

SC: There's hope in them.